Avid hunters, we tramped through cornfields and pastures in

pursuit of pheasant and quail. And in season, we hunted deer

from before dawn until dusk. Our successes were rare but

greatly savored.

–Ira Wagler: Growing Up Amish

____________________________

Hunting. It’s kind of like fishing, I suppose. Maybe worse. It’s the reason a lot of embellished tales get told in every imaginable setting, usually inflicted on unwilling listeners with frozen smiles. When accosted by someone who’s been bitten by the hunting bug, there is no escape. So one may as well hunker down and take it.

And it’s that time of year again. I can always tell at work, because at least one of my yard guys disappears mysteriously every now and then. For a full day, right during the work week. Mixed in with the Amish wedding season here in Lancaster County, things can get a little hectic once in a while. But I try to let my yard guys manage their own schedules, as much as possible. As long as the work gets done, hey, do what you think you have to. I’m a laid-back boss. Maybe too laid-back at times.

It’s not that I’m against hunting, or anything. It would be a good thing if the deer herds in suburban PA were thinned out a bit. I have no sympathy whatsoever for Bambi. And I used to hunt, decades ago. Quite fervently. So I know what it’s all about. But after I left the Amish, it just didn’t seem that important any more. So I quit. Don’t miss it at all, really.

We always had a few guns knocking about, on the farm in Aylmer. Before I was born, Dad bought an old J.C. Higgins bolt action shotgun. 16 gauge, which is an odd gauge these days. And we had a couple of .22 rifles. Used for shooting pests like groundhogs and sparrows and starlings.

The rule at our home was this. We could shoot a rifle after our 12th birthday. We got a pocket watch at 11, and could shoot at 12. I remember well the day my brother Stephen took me out behind our old concrete silo and showed me how to handle the gun. A bolt action .22. I knew how to work the bolt. After some stern instruction and admonition, he handed it to me. I lifted it to my shoulder, pointed it toward the hill to the south. Unclicked the safety. And probably flinched just a bit as I pulled the trigger. Of course, there was absolutely no recoil. Just a sharp “crack” and the quick whine and whump of the bullet as it hit the dirt.

A gun is a tool, like any other. You gotta respect it, of course, or someone could get hurt or killed. Just like one could get hurt or killed by a host of other tools. Like tractors, trucks, and in the case of the Amish, horses or machinery. When I hear the hysterical squeals of gun haters, I shake my head in disbelief sometimes. And disgust. From all their shrill incessant braying, you’d think a gun just up and kills some innocent person on its own any time it takes a notion to. Which is just silly. It doesn’t. Never has. Never will.

But back to being twelve. With my newly granted rights, I soon took to haunting the fields and woods. Always careful, I grew more confident with each excursion. Shot sparrows perched in trees or on the Martin box. And soon developed into quite the fearsome groundhog slayer.

Groundhogs are pests on farms. Dig their burrows, willy nilly, in the pasture fields. We always heard tales of how horses and cows stumbled into those burrow holes and broke their legs. A country legend, I think. I never saw it happen or heard of it actually happening anywhere.

Our pasture fields in Aylmer were dotted with groundhog burrows. I soon honed some pretty impressive stalking skills. Sometimes during the heat of midday, sometimes as the sun was sinking, I walked out with my rifle. Spotted a groundhog sunning himself or just relaxing outside his “doorway.” And began the long, slow stalk, creeping steadily toward my prey when its head was turned. Always freezing on the spot when the rodent looked my way. They didn’t seem to recognize me as a threat, as long as I wasn’t moving. Sometimes my quest was successful; often, though, I came up empty.

One evening after supper, as my sister Rhoda watched from afar by the pasture gate, I crept within ten feet of an alert groundhog. A big dude, sprawled and relaxed on the ground. I saw the hair of his whiskers, and the graying on his hide. Froze and moved as he looked my way, then away. Then I slowly, carefully raised my rifle. Took a careful bead through the open sights. Tensed my finger on the trigger. The rifle cracked spitefully. The frenzied groundhog instantly rolled over and disappeared into his hole. I checked for blood. There was none. I had missed. Too close, I guess.

There wasn’t a whole lot to hunt, in Aylmer. Mostly pests, always open season on those. Groundhogs. Crows. And in the fall, squirrels. Large red squirrels. Rats with bushy tails, really. In time, I graduated to Dad’s old 16 gauge shotgun. In the woods a quarter mile south of our home, I shot my first squirrel one September day. I lugged it home. And learned how hard it is, to skin one. Tough animals, they are. And not particularly tasty, either. After that, squirrels didn’t have much to fear from me.

Back before we moved from Aylmer to Bloomfield, Dad bought a new single shot 12 gauge shotgun at the Canadian Tire store in town. It was a cheap import, but a beauty, at least in our minds. The thing I best remember about that gun happened out of hunting season, one hot summer day.

We kept a flock of broiler pullets in a little shack in the pasture just south and west of the barnyard. White chickens that pecked about in the grass. It was mid morning. And suddenly, someone shouted, “FOX!” We all rushed to the barnyard gate and looked. And there was a fox, tearing back and forth through the squawking broilers, biting one here, chasing one there. The fox seemed weak, staggeringly weak. It stumbled blindly about, chasing, catching and biting chickens.

Such a strange thing was most unprecedented. A fox doesn’t just show up in broad daylight like that. Not unless there is something seriously wrong with it.

We milled about excitedly, watching. Stephen quietly rushed to the house and grabbed the new single shot 12 gauge. Loaded it. Walked out to us. Then through the gate and over the fence. The fox was still chasing and chomping the wildly excited chickens.

Stephen approached the uproar of squawking white feathers. And the fox suddenly stopped chasing chickens. Stopped, and stared with bleared and sickened eyes at my brother. Stephen planted his feet in the classic shooter’s stance. Lifted the single shot 12 gauge. Seconds passed.

And then the fox charged. Right at Stephen. An emaciated little bundle of orange and white, fangs bared. The scene is riveted in my mind as if it happened yesterday. Stephen tensed. And when the fox closed in to about twenty-five feet, we heard the loud “boom” of the gun as the barrel lifted in recoil in Stephen’s hands. The fox instantly collapsed. Dead, silent, on the ground. No quivering or pawing. Just a sad, dead little heap.

No one touched the corpse. Instinctively, we knew. Foxes don’t act like that, unless they are insane. Or unless they have rabies. That afternoon, Dad called a vet. The vet came out within hours and took the fox with him. In about two weeks, we got the verdict. Rabies. The fox had rabies.

No one was infected, including the chickens. Fowl cannot contract rabies. That’s what we learned, way back then. And that was the end of that little incident.

When we moved to Bloomfield, it seemed like a land of Canaan. A land teeming with wildlife, compared to Aylmer. There, my buddies and I tramped the woods and fields for pheasants, quail, foxes, coyotes, rabbits and deer. We pursued the conquest of the hunt with all the energy and passion only the most avid hunters know.

By the time I left in 1986, wild turkeys were moving in. Since then, all that wild game has prospered and multiplied. Southern Iowa harbors some of the biggest whitetails in the country. Deer as big as cows. And bagging a turkey is no big deal these days, from what I hear.

Like I said, I don’t hunt anymore. Haven’t for more than twenty years. Got nothing against it, though, and I mean that. I just can’t see the sense in dragging myself out of bed at 4 AM, and heading out into the cold damp woods to sit and freeze, all because of a rather faint hope that some hapless deer will wander by. If that’s your thing, more power to you. It’s just not mine.

But there is a deeper reason, I think, that I no longer hunt.

It’s because there are so many other options now. Hunting is one of relatively few activities the Amish can pursue for simple enjoyment. At least in many communities. One of the few things they can really get into. And it’s acceptable. After I left, I soon realized there’s a vast smorgasbord out there. So many things to see and do. So many choices.

And as new dreams were born and my interests expanded, some of the old ones gradually faded until they disappeared.

*************************************************

Several months ago, I went to an outdoor evening party. I don’t attend many such events, especially where there will be a lot of strangers. But my good friend, a man who writes for a living, Shawn Smucker invited me. So I went. And quite enjoyed the experience, really.

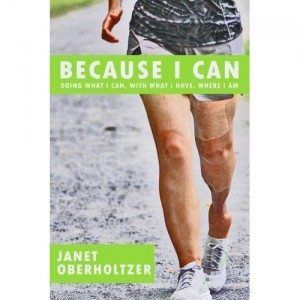

There were indeed many strangers present. Including a lady I now consider a friend, Janet Oberholtzer. Janet and I got to talking. She had heard about my book, and seemed quite interested in my story. Turns out Janet was on the doorstep of having her first book published as well. She has an astounding story of working her way back from a devastating accident that very nearly claimed her life.

Look at the book cover. That’s her leg. And the woman runs. Miles and miles every week.

I don’t usually read books of this type, but I was intrigued. So I got my copy a few weeks back. Read chunks at a time, as best I could in the evenings. Janet’s story is one of dealing with the really brutal stuff that never hits most of us. Hers was an extraordinary journey. After the accident, after beating the odds just to survive, Janet was told that her left leg would probably have to be amputated. That’s how bad it was. But she prevailed through it all. It was a long, tough slog.

After you walk through something like that in your life, there are a few things that could happen. You could just give up. Alive, but not really. Or you could function at some level, an emotionally scarred wreck. Or you could choose to live, to heal, to attack the obstacles, to reclaim your life, to never surrender to the darkness. Which is what Janet chose to do. And because of her choices, here is her story.

The thing I most appreciated about the book was Janet’s raw honesty in describing every stage of her journey back from the brink of death. It permeates the narrative.

I’m glad I went to Shawn’s party. And I’m glad I met Janet. You can meet her too, by ordering her book on Amazon.

Share

“If every family would just do as they pleased,

what kind of church would we have?”

-Bishop Sam Mullet

________________

I was about as floored as anyone, I suppose. The media sure had a field day with the juicy reports. Amish people invading the homes of other Amish people and cutting off the beards of the men. And, at least in one case, forcibly cutting the hair of the women in the house. The news flashed in headlines all across this continent. And across the world. Befuddlement ruled, mostly. Such shocking stuff had never been heard before. Surely it was all just a farce. It wasn’t, sadly.

I instantly and instinctively realized the story would be good for my book sales. And almost immediately, my Amazon numbers, which had been languishing between 10,000 and 20,000 in the rankings, rocketed up. For a couple of weeks now, Growing Up Amish has pretty much been hanging right in there between 3,000 and 10,000 in the rankings (watch it plunge back to where it was before, now that I went and said that). I don’t know exactly what that means in real hard numbers. A dozen books a day, maybe. But when the subject of the Amish hits the headlines, there’s no such thing as bad publicity, not when it comes to sales of my book.

Along with a host of Amish and ex-Amish people, I read in disbelief as the details trickled out. And mostly, I won’t rehash those details in any depth. Just give my take on the entire sordid episode.

I did make some calls to few trusted contacts in Holmes County, though. Just to get a first-hand feel of all the buzz. And to try to sort the actual facts from all the media hype. My contacts were most helpful. One of them was very closely involved in the aftermath of these events.

It’s a terrible thing, to really grasp. People entering your home, and cutting off your beard. I mean, that kind of religious zeal went out the window, at least in the West, centuries ago. What is this, the second defenestration of Prague? Back then, they committed all kinds of atrocities during frenzied religious disputes. In a way, I couldn’t help but laugh at the mental picture in my head, though, of these beard-cutting incidents. How whacked can you be, to think you’ll get away with something like that in today’s world? Sheer madness, in every sense of the phrase.

It all stems from one man, and that one man’s decisions. Bishop Sam Mullet. From the pictures I’ve seen, a well-fed man. Not plump, particularly. But smooth. And well spoken. Looks Amish as they come. Large nose. Weathered but not unhandsome features. A patriarch with a full flowing beard that widens as it lengthens, well combed. Adds gravitas and all, such a beard. Could even be a source of pride, I’m thinking. Wonder how Bishop Sam would feel if someone forcibly cut that majestic beard from his face.

And there he stands, addressing the media. Confident. Arrogant. Smug. Yes, this was a church matter. No, the law shouldn’t be involved. And no, his group is most definitely NOT a cult. How could anyone suggest such a scandalous thing? And of course he didn’t order the attacks, didn’t order his followers to go cut beards and hair from Amish men and women in the sanctity of their homes. Of course not. But yet, his denials echo hollow. (Since that one hour-long interview, he’s been awful quiet. I bet his lawyer told him to shut up.) Why then, did his followers do such a preposterous thing? Did they just dream it up on their own? And follow through, without his blessing? Maybe. But I think not.

And here, it might be good to speak of a bit of background history. Of who Bishop Sam was way back when, and who he is today. My conclusions are my own, and should not be construed as anything other than my opinions.

The timeline of events seems a bit murky, so I didn’t spend a lot of time researching the dates and such. Because they don’t really matter that much, not to the essence of the story. From my Holmes contacts and from a New York Times article, I pieced earlier events together the best I could. So some of my background “facts” may be a bit off, as to exactly when they happened.

Bishop Sam emerged from the strict plain Amish settlement in Geauga County, up near Cleveland. The Geauga Amish have always had an unsavory reputation. Just a notch above the Swartzentrubers. “Low” Amish. Uncouth. Rough. Hard core, far more so than the mad bishop who tormented me all those years ago. Their laughter is hard and mirthless. Many drink. Or smoke. Or both. And their youth practice bed courtship. All the bad stuff my father raged against in his writings, all his life. That’s Geauga.

Some decades ago Bishop Sam moved to a similar settlement in Fredericktown, Ohio. Somewhere along the line, he was ordained, first as a preacher, then as bishop. I have no idea when. He relished his new position, and reveled in his newfound power. And ruled over his frightened huddled flock with a crushing iron fist. Old Testament style.

At some point, then, in Fredericktown, for some reason or other, Bishop Sam got restless. In time, he made plans to move away to another place and take his flock with him. And he did. Moved to Bergholz, Ohio, with around fifteen other families. And so they settled in the Bergholz area, Bishop Sam and his little group of pilgrims. Set up their own little world, and their own little community. Revolving around the dictates of one man. The man.

The Bergholz community may not have been isolated at its inception, but it soon was. Before long, the rumors started trickling out. Murmured stories of what went on. Brutal things. Despicable, horrifying things. I won’t recount them, because they may have been just rumors. Or maybe not. Inside the Amish lines of communication, details get embellished sometimes. A lot, actually. It’s called gossip. But the core of that gossip is usually based in some seed of truth. It is true that Bishop Sam successfully defended himself from charges of child abuse, and then turned and sued the local sheriff for $2 million dollars. He didn’t get that, but he did win some sort of judgment for a far lesser amount.

Then, about five years ago, there was trouble in Thug-land, uh, Bergholz. I have no clue what that trouble was, but Bishop Sam suddenly and stridently excommunicated some members of his church. Perhaps because they dared to stand up to him. Or maybe they just wanted to leave, to move out. Whatever. But he just kicked them out. Perhaps he really believed that was the right thing to do. Most likely, though, he simply could not brook any form of dissent. Or departure from his cultish enclave.

The excommunicated members were deeply grieved. Felt they had been wronged. So they approached some other bishops in their Amish fellowship. Told their stories. They must have seemed credible, because the bishops were concerned enough to launch an investigation. And they found that the excommunications had indeed been unjust. They stepped in to correct Bishop Sam’s harsh and hasty edicts.

And all was functioning as it should have, in the Amish way of things. There are structural safeguards. Sometimes they work; many times they don’t. This time, it seemed they had.

Bishop Sam, however, reacted in a manner most unbecoming. Some say his response was an explosion of raw rage and fury. Instead of accepting the rebuke of his peers, he refused to acknowledge their authority. Wounded, as a wolf among sheep, he simmered and stewed and chafed. He simply could not and would not let it rest. Or let it go. And his little frightened flock huddled low and endured the turbulent spasms of his deranged and egotistical rage.

His will was law in his little commune, by all the accounts I’ve heard. Still is, for that matter. The thing festered in him, how he’d been so mistreated by the other bishops. How his authority had been challenged. How his decision had been overturned. And somehow, through the years, someone in his group came up with the idea of extracting revenge. Cut the beards and hair of those who had wronged him. Not saying the plan was Bishop Sam’s idea. He denies it. I can’t prove it, one way or another. But I’d bet the farm that it was. Not that I own a farm. But if I did, I would bet it.

And so the nefarious plot played out like it did. In several different areas, within a span of a couple of weeks. Gangs of men forcibly entered the homes of several, mostly elderly, Amish bishops, the ones who had been involved in overturning Bishop Sam’s excommunications. Held them down and cut off their beards. In at least one instance, the gang included women. They assaulted the household women and at least one young girl and snipped their long hair. At least two of Bishop Sam’s sons, and one son-in-law, were arrested and charged. As were a few others. From what I’ve read in the news reports, all of them are free on bail.

Obviously Bishop Sam was a charismatic or otherwise mesmerizing man, or he never could have moved into the role of social-outcast leader and kept so many loyal followers. And obviously, his sons could never break free of him. They see with hollow, vacant eyes, believing in nothing but their father. They are enslaved to him. A man of his character would never release control of his sons under any circumstances. And they never developed the backbone to stand up to him.

That’s their loss. Big time. They could have been so much more. Could have been the men they were created to be. But they threw it all away. Sacrificed themselves to their father’s will. For nothing.

As far as controlling his sons was concerned, Bishop Sam wasn’t that different from a lot of Amish fathers, really. Not in the aspect of absolute control. He just took it further, pushed it way outside the lines. So far outside the lines that he now stands as a caricature of the Amish culture that birthed him. A bitter, violent controlling man. And this time, I think, he probably pushed it too far. It’s going to come back and bite him. It just is.

This time, he miscalculated badly. He figured his goons could slip in and assault his perceived enemies without any repercussions. That the news would not spread beyond the local Amish communities. The Amish don’t believe in calling the cops, or pressing charges. So he could get away with it unscathed, he figured. There was no way he or any of his thugs would face charges. That’s what he thought. He was wrong.

The law wants him, bad. As a libertarian, I am strongly inclined to leave people alone, mostly, to reap the consequences of their choices. As I strongly prefer to be left alone, mostly. And, perhaps stemming from my Amish roots, I’m usually extremely reticent to get the cops involved anywhere for any reason. But this guy, well, it would be good if they nailed him. Put him away for a while. Providing they can produce some hard evidence, of course. Hearsay and gossip alone are not enough. The evil in his heart is not enough. They have to be able to prove that his influence and his commands were the driving force in these attacks. An extraordinarily high hurdle. Absent that, the man cannot be judged guilty in a court of law.

He knows who he is. We don’t, not really. We can only surmise from what we see and hear. Sometimes, even in the most “clear cut” cases, our perceptions can be deceptive.

It will be interesting to see how it all shakes out. Bottom line, though, is this. Bishop Sam and his little gang of thugs are not Amish. No more so than I am. Sure, they dress Amish. Talk Amish. Look Amish. But they have violated one of the foundational tenants of the Amish faith. Nonresistance. They have embraced violence, and there is not a single group anywhere in the “real” Amish world that would fellowship with these guys. Or have much of anything to do with them. Not one. They stand alone. As the renegades they are.

And that’s pretty much all I got to say about one of the most bizarre incidents ever to come down in all of Amish history.

*************************************************

All righty, then. A couple of book signings to announce. Coming up in November. On Saturday, Nov. 19, I will be at the Barnes and Noble Bookstore at the Red Rose Commons in Lancaster, PA. From 3 PM until whenever people stop coming. Hope to see some of you locals there. And maybe even some non-locals. Remember, a lonely author sitting there twiddling with his pen and smiling hopefully is not a pretty sight. Don’t let it happen to me.

And then, the following week, the week of Thanksgiving, I’m going “home” to Bloomfield, Iowa. First time since the book was published. My nephew, John Wagler, has invited all his cousins (my nieces and nephews, a good many of whom will show up) and several uncles, to his home for the holiday. I doubt I will hang much in the Amish community, except for stopping by to see my brother Titus. I’ll definitely do that. Otherwise, I’ll probably lay low.

Anyway, I will have a book signing in Bloomfield on Friday, Nov. 25, from Noon until 3 PM. (NOTE: THIS DATE HAS BEEN CHANGED FROM TUESDAY, NOV. 22nd TO FRIDAY, NOV. 25th.) I’ve rented the Get-Togather Room, a converted store front on the north side of the town square. All are welcome to bring their copies, and I will have a couple of cases of books with me for those who wish to purchase one.

I’m nervous and excited to be returning to Bloomfield. Most of the old haunts are gone now. Chuck’s Café in West Grove was demolished years ago. The community is no longer what it was. But the memories remain, stark and vivid. And many of my old English friends are still around. I can’t wait to hang out and reminisce.

Share